Lecture by Nani Jansen Reventlow — 9 October 2025

I couldn’t be more thrilled about the theme that was chosen for this year, “radical social justice”. Especially since Dr King was radical in his vision for racial, social, and economic justice – much more so than the way in which his work is often quoted and referenced by many people nowadays.

Dr King and the civil rights movement he was part of were doing their important liberation work in the United States in an era that was characterised by great economic prosperity following the two world wars. This prosperity was not shared equally, however, and went hand in hand with systemic disenfranchisement, racial segregation in schools, housing, and public spaces, and persistent economic inequality for Black people in the United States. Outside the US, a wave of decolonial struggles had started to unfold, war was being fought in amongst others Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, and the Cold War was in full swing.

Despite the significant changes that the civil rights movement and others across the world have brought about, the state of our world today unfortunately doesn’t — yet — lend itself to much optimism. Our climate is on the brink of irreversible collapse, and we are seeing the mass extinction of thousands of species. We failed to make necessary changes when the Covid-19 pandemic laid bare the structural inequalities in our societies, and we never delivered on the promise of the 2020 racial justice uprisings in the US and Europe. We are quietly consenting to letting genocide unfold in Gaza, Sudan, Myanmar, China, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. We are failing to support and protect those fleeing areas made uninhabitable due to the climate crisis, war, and other disasters we created. More and more voters around the world are electing openly racist and xenophobic parties into power, institutional racism is left unaddressed, and intolerance across the board is becoming increasingly normalised. Masks are coming off, as is illustrated by the open display of fascism in the US, the UK, and increasingly here in the Netherlands.

In times like these, it can feel tempting to despair. “The world is a mess, too big a mess to clean up, so why even bother?” And: “I am just one person — what difference can I possibly make?” Sentiments like these also make us want to look for someone else to come in and fix things for us. A charismatic saviour who can lead the way out of this mess we made.

I said “the mess we made” and: that is good news. Because, since we are the ones who made it, we are also the ones who can clean it up.

We are the heroes we need — and each of us can be the revolution.

Today, I will talk about heroes and hero worship, leaning into discomfort and imperfection, and about the activism we see and that which gets invisibilised. I will discuss why hero worship is dangerous for our pursuit of a just world, and what each of us can do to change things for the better, starting right here and right now. My hope is that, at the end of this evening, you will feel energised, re-energised, committed, or recommitted – whatever is applicable to your situation — to do what you can do in pursuit of radical social justice.

As I said at the outset, it is an honour to deliver this lecture marking the legacy of Dr King, whose tremendous work for civil rights continues to inspire countless people to this day. Heroes like Martin Luther King inspire, and their stories support us with great motivational narratives and storytelling that help reinforce our belief that it is possible to do something remarkable, that we can create big, systemic change in the world.

In 1967, the year before Dr King was assassinated, novelist, poet and social activist Alice Walker wrote the following in her essay “The Civil Rights Movement: What Good Was It?”:

“Six years ago… the Civil Rights Movement came into my life. Like a good omen for the future, the face of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., was the first black face I saw on our new television screen. And, as in a fairy tale, my soul was stirred by the meaning for me of his mission …”

Because Dr King kept working to reach people through the principles of nonviolence, love, and brotherhood, despite the danger to himself and his family, Walker wrote, “I saw in him the hero for whom I had waited so long”. This, she says, was the reason she “fought harder for my life and for a chance to be myself, to be something more than a shadow or a number, than I had ever done before in my life.”

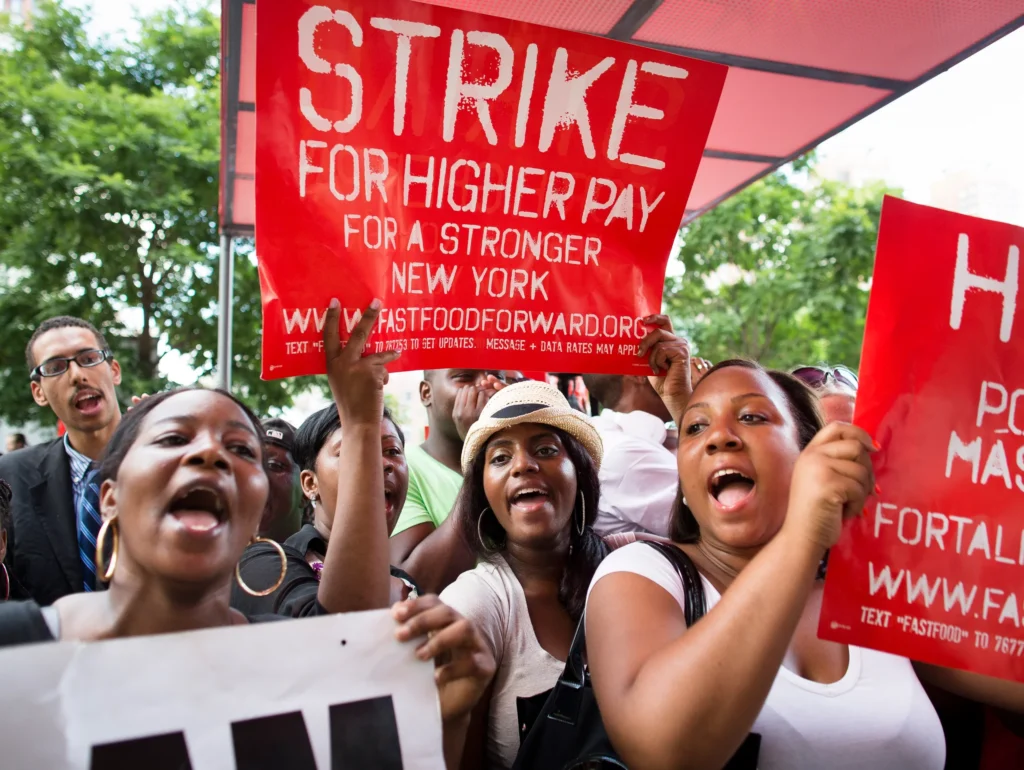

As we all know, Dr King continues to inspire and motivate those fighting for justice. When fast-food workers in the US were striking for fair pay in 2021, one of them stated: “I’m striking today to carry on Martin Luther King Jr.’s fight for racial and economic justice in this country, which means every working person earns a living wage and has a job with dignity”. Other activists who referenced his work in recent years include climate activist and initiator of the Fridays for Future movement Greta Thunberg, abolitionist and co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement Patrisse Cullors, and disability and social justice organiser Lateefah Simon who recently became the first blind woman elected to United States Congress.

And yet: while the presence and storytelling of heroic leaders like Martin Luther King are important ways to inspire and motivate us, there is also a downside to consider in focusing on hero figures.

Our collective imagination seems to only leave room for one archetype of authority and one image of what being a leader looks like: a charismatic, male, heroic figure. The saviour trope is an attractive vision that the press, entertainment industry, and social media are happy to repeatedly present us with. It fits in with the ‘hero’s journey’ narratives we are familiar with from mythology, as well as the salvation and messiah figure central to many religions. It also is a convenient way of distilling complex challenges into something an audience can more easily wrap its brain around. This, however, weakens our ability to engage with multifaceted issues such as change and resistance in anything other than a simplistic and piecemeal way.

This harms our collective progress towards liberation in two ways.

First, because it gives us a “role model” that only few of us can recognise ourselves in and that even fewer of us will be in a position to emulate. We should be able to see ourselves in heroes reflecting the full breadth of identities and positionalities in our societies. We are currently missing out on the stories of the many remarkable Black women, Indigenous women, and women of colour who, often unacknowledged, unsupported and frequently invisibilised, have done and continue doing crucial worldmaking and changemaking work.

“My theory is, strong people don’t need strong leaders.”

– Ella Baker

Second, because it undermines the belief in our own power and agency to pursue a better world. Focusing on heroes can distract us from harnessing the power each of us has to bring about change.

It draws our attention away from what we can do — by ourselves and in community — without a messiah figure to lead the way. It is my thesis that each of us acknowledging that power we have and embracing the responsibility and accountability that comes with it, is what will make the difference between us being able to turn the course we’re currently on with this planet or not.

Some of this may sit uneasily with some of us: how can I both stand here acknowledging the enormous power of the legacy of a hero, Martin Luther King, and at the same time argue that hero worship doesn’t serve us? It is exactly this discomfort that we all should be leaning into more.

We have a tendency to want to categorise everything as either perfect or as wrong, flawed. However, there are usually more dimensions than just the ones we love about even our most cherished fables. Let us take the opportunity to practise sitting with this discomfort right now.

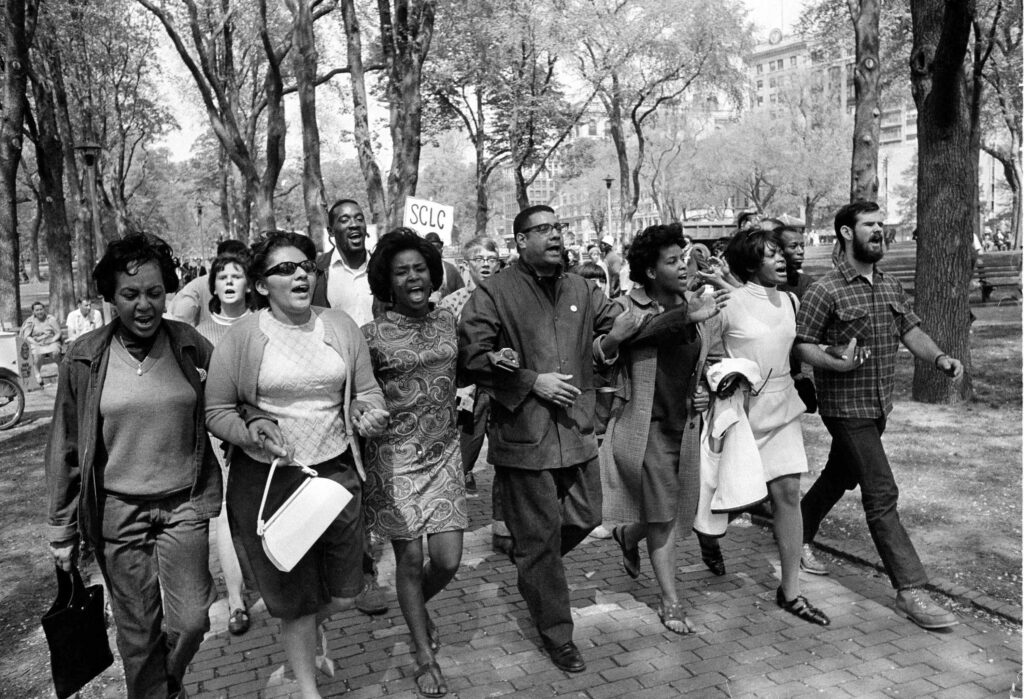

No movement is perfect, and the US civil rights movement was no different. Movements also don’t have to be perfect — human work is messy, it is flawed, and: it is beautiful.

A big flaw of the civil rights movement was the way in which it invisibilised the important role women played in it. Like in many iconic liberation struggles — past and present — sexism was pervasive. Women were pushed to the sidelines and into supporting roles, yet they made up an important part of the resistance.

This is easily illustrated if we think of the names from that movement we are frequently reminded of. Those are mostly the names of men. This of course includes Dr King, but also Malcolm X, John Lewis, Thurgood Marshall, Fred Hampton, W.E.B. Du Bois, and many more. Looking beyond the US, we see similar patterns being replicated across freedom struggles. From Kwame Nkrumah and Patrice Lumumba to Mahatma Gandhi and Che Guevara: the main names we know are of the larger-than life men who spearheaded revolutionary movements.

Names that many of us are less familiar with are those of the women who played key roles in civil rights and decolonial struggles. Within the civil rights movement, I am thinking of women such as

-

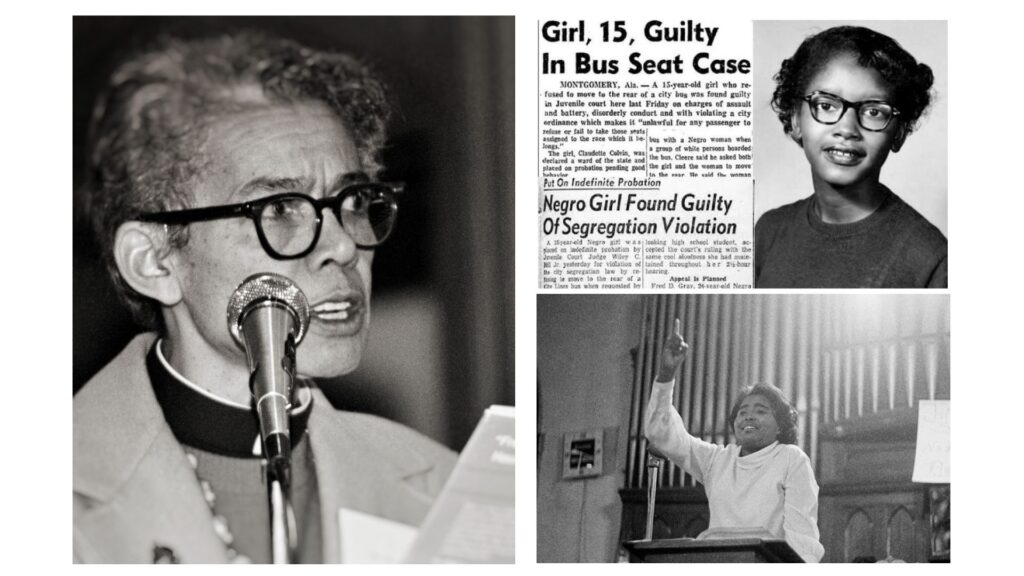

- lawyer, priest and civil rights activist Pauli Murray, whose work informed the arguments made in Brown v. Board of Education, the US Supreme Court case that confirmed that racial segregation in schools was unconstitutional;

-

- activist Claudette Colvin, who was arrested at 15 years old for refusing to give up her seat to a white woman on a segregated bus 9 months before Rosa Parks’ refusal to do the same sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott;

-

- and womanist theologian and Baptist priest Prathia Hall, who was one of the few woman field organisers of the influential Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Hall also led the prayers at a commemorative service where Martin Luther King heard her say “I have a dream” – words he got her permission to use and ended up making history with.

Examples of women who played important roles in the freedom struggles taking place across the world include

-

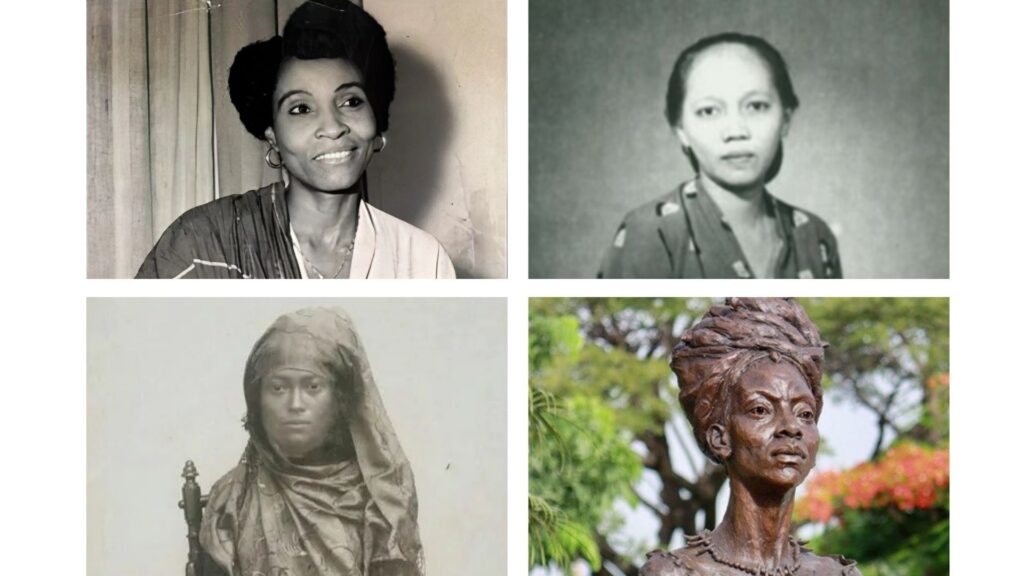

- feminist and political activist Margaret Ekpo, who was actively involved in the struggle for Nigerian independence, and fought for women’s rights;

-

- independence fighters like Umi Sardjono and Cut Nyak Dhien who resisted the Dutch colonisation of Indonesia;

-

- and Jamaican revolutionary Queen Nanny of the Maroons who led a community of formerly enslaved people in successful guerilla warfare against the British colonisers.

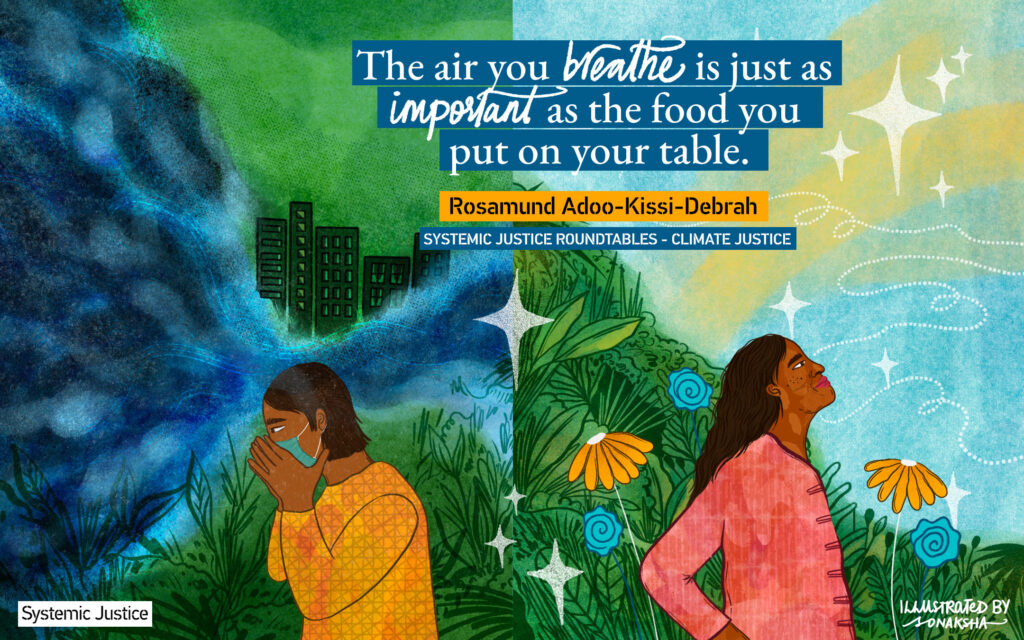

On a more local level, we also see women’s leadership in the work we do with community partners at Systemic Justice, the organisation I founded in 2021: women are the driving force in much of the changemaking community work we are supporting with legal strategies. Be it resisting air pollution and other forms of environmental racism, or fighting for access to decent housing and equal education — we consistently see women at the forefront of organising and resistance.

However, relatively few of us will know of the many Black women, Indigenous women, and women of colour who have played key roles in activism in all walks of life, especially if our main source of information is the mainstream media. This is not unique to the civil rights movement, nor is this a historical issue: it has been a prevalent dynamic around the world that is still happening till this day.

The work of women in the civil rights movement was pivotal in pursuing the goals of the movement and in determining what those goals should be. Martin Luther King’s wife Coretta Scott King is a great example of this. She is often cast in a supporting role. But, even though she was expected to first and foremost be a wife and mother and was asked to “step aside” after her husband’s assassination, she was an activist before they met. Her activism in many ways drove and shaped the positions that Dr King became known for. Coretta Scott King was a fierce proponent of socio-economic rights, spoke out forcefully against the Vietnam War long before her husband did, and after his death she continued working on issues such as welfare, the intersections of race and gender, the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, and the right to same sex marriage.

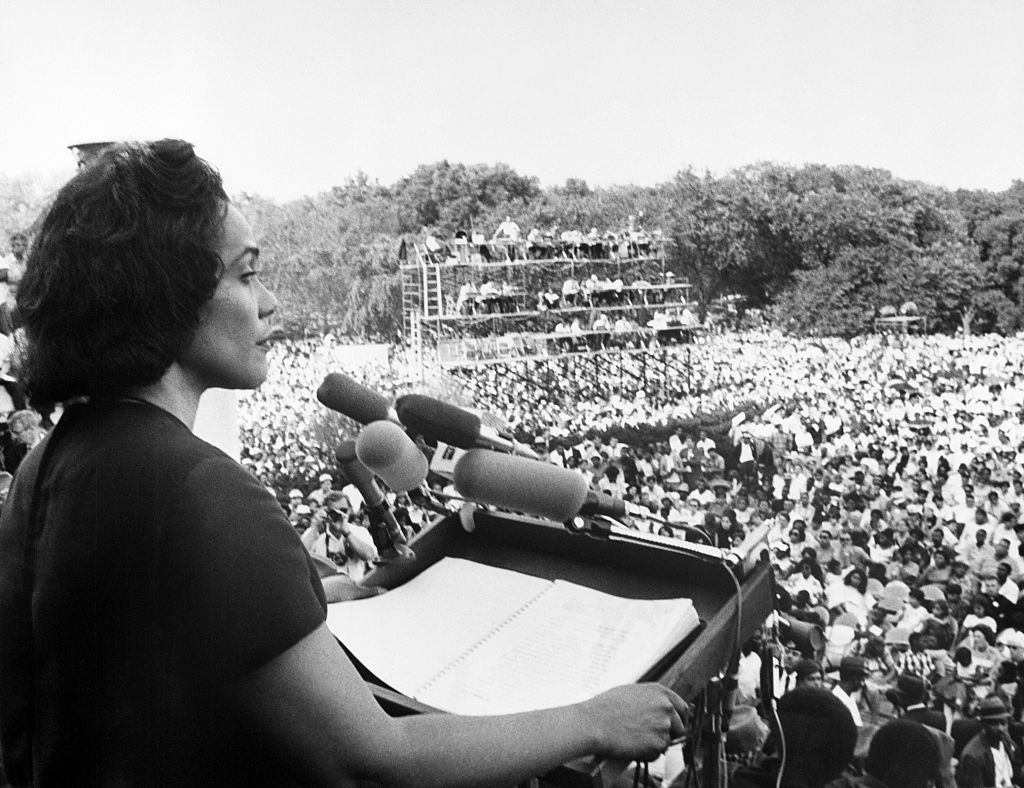

Despite all of this, she did not lead the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom together with Dr King in 1963. Tens of thousands of women participated in the March, but none of the women civil rights leaders marched in the procession with Dr King and the other male leaders, nor were any of them invited to speak to the crowd. Instead, they were asked to march on an adjacent street and to stay in the background.

The March was supposed to be a men’s march, with only a small supporting role for women, even though women fundraised to make it happen and played a crucial role in planning and organising it. Rosa Parks, whose refusal to give up her seat sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott that launched Martin Luther King’s prominent role in the civil rights movement, was given a brief acknowledgement along with a handful of other prominent women in the movement, but none of them got to speak. The “wives”, including Coretta Scott King, were only allowed to sit beside their husbands on stage.

And this is where we have to practice sitting with complexity and discomfort. The March was hugely impactful: it mobilised over 250,000 people. It spurred on the adoption of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, two landmark pieces of legislation that outlawed discrimination on various grounds in key areas of public life. It was a pivotal moment in the civil rights struggle.

And at the same time, only some of the people who helped make the important changes I just mentioned happen are etched into our collective memory as the “heroes” who led the way towards that change. But they were only part of the picture, and not telling the fuller story makes it more challenging for each of us to see ourselves as agents of change, the ones who can alter the status quo and fight injustice.

We are the heroes we need — and each of us can be the revolution. We are the leaders, the heroes, the changemakers — whatever you choose to call it — that we need.

That may sound like a nice idea, but some of you may ask: “what does this mean in practice?” Others might say “all that changemaking business sounds very nice, but I have a life, a job, a family; I have a degree to finish, I have bills to pay – I have responsibilities. Where am I going to find the time to get involved in activism?”

First of all: if you are able to ask this question, you should consider yourself very lucky. Most people on the frontlines do not get to choose their activism: they are resisting injustice out of necessity. The Indigenous groups worldwide resisting green colonialism did not choose their fight. Nor did the inhabitants of island states battling rising sea levels. Or the Roma communities living on polluted land, excluded from basic services such as clean water. Their work is a fight for survival, not a career choice.

Second: our world is on fire. Literally. According to the latest projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) global temperatures are likely to rise on average within a range of 2.1 °C to 3.5 °C in the coming decades, even under the most favourable scenarios. The Union of Concerned Scientists has said that this means we could experience up to eight feet of sea level rise by the end of the century, which would leave some entire island nations submerged. So: yes, we all have responsibilities. And: the main responsibility we all have now is to change the destructive course we are on while we still have a small window to do so.

Each of us can make what American civil rights activist John Lewis called ‘good trouble’ in different ways. We don’t all have to take to the streets, chain ourselves to an oil tanker, throw a can of soup at a painting or rush to court to bring strategic cases. There is not a one-size-fits all way to engage: we all have our strengths to bring to the table, and we should use the ones we have where we can. It’s okay to do what falls within your sphere of influence and what suits your particular skills and temperament. In fact, chances are you’ll stick with it for longer if you do something you enjoy or are good at; which is what we need. We need a tapestry of sustained activism to make deep, lasting change.

What I will share with you now are suggestions. They can either help you get started in finding your way into activism, reinforce the journey you are already on, or maybe just give you a few new ideas. They are not rigid guidelines or prescriptions: take from it what works for you, adapt it, mix and match it with other practices — make it your own.

1. Educate yourself

To create real, lasting change, we need to understand the root causes of the injustices we’re challenging. Last year, I published a book called “Radicale rechtvaardigheid” or in English: “Radical Justice”. The “radical” in the book’s title comes from Angela Davis’ words that “radical simply means ‘grasping things at the root’. If we don’t invest in learning what is causing the challenges we’re facing, we run the risk of chasing fixes that are merely cosmetic or superficial.

Educating yourself is a continuous process of learning, unlearning, and reflecting within a moving landscape, and of leaning into — yes — the discomfort that comes with it. While that is not easy, it is important to (1) do the heavy lifting yourself and (2) always dig a little deeper than what you find at first sight. Don’t expect marginalised folks to educate you and don’t rely on mainstream media to tell you what’s what.

2. Be bold and unapologetic in your vision for change

Understanding the world is important, but, as Karl Marx said, the point is to change it. All liberation starts with dreaming up a vision of what things should look like. What will the world look like the day after the revolution? Dreaming and worldmaking are important steps in setting the course for the future we want to inhabit.

And our dreams need to big, bold, and beautiful. When an Indigenous community in New Zealand first proposed to extend legal rights to nature, most people had no idea what nature rights were, could not fathom how a river could have legal personhood, let alone imagine a legal system that would recognise it. But the Māori community of Whanganui’s fight to have their local river recognised as a living entity inspired a global Indigenous-led mass movement to recognise the rights of nature – the recognition that our ecosystems, not just humans, have rights – everywhere. Since 2017 the movement has garnered landmark rulings in India, the US, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, Canada, and Spain.

3. Be practical and let go of perfectionism

That your vision is big does not mean that your actions have to be grand as well. A good place to start in finding your place in the revolution is considering your sphere of influence.

That your vision is big does not mean that your actions have to be grand as well. A good place to start in finding your place in the revolution is considering your sphere of influence.

“Each of us must find our work and do it.”

– Audre Lorde

We need to continuously check in with ourselves to make sure we are doing what we can, where we can. And: you don’t need to have a perfect plan or to have a precisely mapped out trajectory of how to get to your dream vision to get started. Perfectionism is one of the ways in which white supremacy culture blocks the path towards liberation.

4. Solidarity is everything

No justice or liberation struggle stands in isolation. I spoke about the fight for climate justice earlier, which is interconnected with the instances of genocide I referred to. The genocide in Gaza is also a climate catastrophe: the Guardian reported earlier this year on a study showing that “the carbon footprint of the first 15 months of Israel’s war on Gaza will be greater than the annual planet-warming emissions of a hundred individual countries”. The genocide in Congo is fuelled by the extraction of minerals. These genocides, and with them other genocides and countless conflicts, are rooted in the racial capitalist tracks laid by imperialism and the global slave trade that our world still runs on today. It is all connected.

So do not focus exclusively on your own struggle but make space for showing up in solidarity with others.

The interconnectedness of struggles and the need for cross-movement solidarity have repeatedly been acknowledged and acted upon by movements. Angela Davis, Malcolm X, and many others from the civil rights movement saw the interconnectedness between the Palestinian struggle and the fight against racism and a militarised police force in the United States. And the Palestinian Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement, which was inspired by the South-African anti-apartheid movement, has worked in coalition with feminist movements, trade unions, universities, artists, and many others across the world.

5. Trust that your contribution matters, both in scale and in timeliness

All contributions, however small they may seem, matter.

When it comes to scale: I referenced a number of decolonial and liberation struggles, but we can also see changes on a smaller scale. For years, communities and activists across the world have been reclaiming the topography of their cities: changing street names from the names of colonies, slave holders, and historical racist figures to those of revolutionary anticolonial leaders, battles and protests, and liberatory moments in history. Street names are being contested and re-appropriated as sites of resistance to imperial narratives and the whitewashing of history. Because to imagine a different future is to inhabit it — literally.

“Many historical struggles were carried out by people operating in the full knowledge that they would never see the intended goal that they sweat and bled for… The arc of the moral universe will not bend itself… It will be bent by deliberate effort and political struggle if it will be bent at all — and there’s no other hands to do it but ours.”

– Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò

Concerning time: we have to accept that not all of us will get to see the change we’re working for in our lifetimes. Deep change can take generations, and many of the “wins” and “watershed moments” we celebrate were built on so-called losses and the kind of organising that doesn’t grab headlines. This also means that we must, at times, accept the loneliness that comes with resistance work. In hindsight, it always looks like movements for change operated in unison, with everyone likemindedly pursuing the same goal. That is not true. I find that realising that we are building on work that was started before us, and that our work will be continued by others after we’ve gone – the idea of being a good ancestor — can bring important perspective and support in those moments when we feel alone or isolated.

Before we move to close this lecture, I want to flag the relative nature of perspective. History may look upon you unfavourably, too favourably, or not remember you at all — this shouldn’t matter for what you do in the here and now.

“One has not only a legal, but a moral responsibility to obey just laws.

Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

– Martin Luther King Jr

When Martin Luther King received his honorary doctorate from the VU, he was labelled as a terrorist in the United States. In 1966, a year after the Voting Rights Act was passed, a poll found that 72 percent of white Americans had an unfavourable opinion of him, and 85 percent said that demonstrations by Black people on civil rights hurt the advancement of civil rights. Dr King was jailed 30 times and was repeatedly called “anti-Christian,” “pro-Communist,” and “extremist.”

This narrative has obviously changed dramatically over time. And, ironically, we are now seeing how the — often softened and stripped of their radial perspective — narratives about the once-maligned civil rights movement are being used to disqualify new movements, such as Black Lives Matter, by comparison. Like the civil rights movement at the time, it is now their turn to be called reckless, unreasonable, and out for their own gain.

“Struggle is a never-ending process.

Freedom is never really won, you earn it and win it in every generation.”

– Coretta Scott King

I started today’s lecture with some rather pessimistic reflections on the state of the world. The challenges we’re facing today underline the veracity of Coretta Scott King’s words that “Struggle is a never-ending process. Freedom is never really won, you earn it and win it in every generation.” So let us all get in motion to earn the freedom we want and need for this generation, building on the important work that generations of freedom fighters have done before us.

Things may seem much worse than they have in a long time, but that also means that we have an opportunity to get more people involved in the struggle. The unravelling we’re witnessing will leave no one unharmed, so also those of us who have been able to keep ourselves safe until now will need to step up. Does what you are reading, seeing, hearing in the news each day make you angry? Great. Use that anger as a catalyst for change. Anger is a wonderful forward-looking emotion, the activating sibling of hope. We need to take that energy and use it to organise and build a mass movement around our vision for a community, a country, a world built on a foundation of human rights and racial, social, and economic justice. The time to do this was yesterday, but today is not too late.

* * *

Nani’s book Radical Justice is available in Dutch at your local bookstore and available for pre-order in English.

Here are some suggestions to learn more about some of the trailblazing Black women, Indigenous women, and women of colour who made history:

-

- The Hidden Histories with Nova Reid podcast, which tells the story of Queen Nanny of the Maroons, Olive Morris, and other trailblazing Black women https://www.novareid.com/hidden-histories

-

- The Know Your Caribbean website, podcast, and Instagram account by Fiona Compton https://www.knowyourcaribbean.com

-

- (Dutch) F-site, which offers materials for a better informed school curriculum and a podcast “De geschiedenisles die je nooit hebt gehad” https://www.f-site.nu

-

- The Black Archives, which maintains an extensive archive, and organises exhibitions and events